HOW WE GOT HERE, WHERE WE'RE GOING

The story of how the Sowell project came to be, and where we are now.

Actors normally wait tables until they make it.

I did the reverse.

2020. I'm an up-and-coming star in New York City. Over the prior 3 years I’d experienced a sudden and explosive career growth: starring on TV opposite actors I’d admired as a kid; sought after by Tony Award-winning directors; attracting award recognition; even winning effusion from luminaries such as the late Stephen Sondheim. A decade after diving into the turbulent waters of NYC's entertainment industry, it seemed I was finally beginning to tread water.

Then the world shut down.

I spent the first 3 months of 2020 preparing for a viral apocalypse.

Canned goods? Check. Toilet paper? Stocked. Masks? $75 for a box of 50 from Amazon. I badgered friends and loved ones with statistics. I kept hand sanitizer at the ready. I quit shaking hands at auditions. I was horrified that no one else took the lingering plague as seriously as I did. Eventually everyone else caught up. But just as I’d gone against the grain in my pandemic preparation, I began to challenge consensus regarding what society was being forced into doing in order to “flatten the curve” and “stop the spread.”

As mystified as I was that few people seemed aware of looming doom, I became equally mystified at the collective refusal to weigh the costs and benefits of pandemic policy, or to consider the trade-offs of such actions in the short or long-term. I was a bleeding heart artist, but I was thinking like an economist. What would be the social, emotional, and psychological costs of induced hysteria and prolonged isolation?

Equally unconsidered was the swift, sweeping reaction of show business to the death of a black man in Minnesota. Although more information emerged that challenged the initial narrative of George Floyd's death, the impact of the initial video was instant and explosive. Fiery manifestos were penned, recriminations and apologies offered, and racial quotas were mandated.

Suddenly a field wherein I'd long found a home, and which had just began to offer me a window into a good life—had declared itself irredeemably racist and in need of drastic reform.

At this point I began to speak up.

It was the worst mistake of my life.

I'd long had a public Twitter profile where I posted information on my performances. No one cared. I also had an anonymous account where I offered my true opinions. No one cared about that either. But in 2020, after I began opposing the fast-prevailing dogma under my real name, things changed quickly. I met other disillusioned liberals, found myself on various podcasts, including Triggernometry and TimcastIRL. Thus began my social and professional suicide.

By the time mandates for the COVID vaccine took hold in the entertainment industry in 2021 I was already resolved to refuse. I'd already recovered from the disease in December of 2020. Theatres began tip-toeing back into production, and asking whether and when prospective hires would be vaccinated against SARS CoV2. For some reason, prior infection was never considered.

Eventually my manager—whom I thought I'd work with for the rest of my career—dropped me. My voice-over agent slinked off quietly. Even my therapist ghosted me. In 2019 I was finally making a name for myself in New York City. In 2021 I was waiting tables in Atlanta, GA.

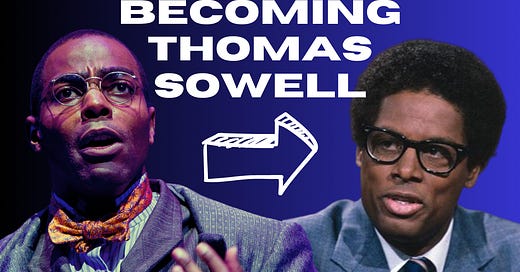

I spent the next several years adrift. I'd passed the landmark age of 40—with a shattered past and no future. Treated to drinks by my friend Craig, I casually mentioned an idea I'd dreamt up years ago but never seriously considered. I'd thought of how actors like James Earl Jones and Laurence Fishburne had done one-man shows about prominent black figures (in this case Paul Robeson and Thurgood Marshall, respectively). I said “what if I did a one-man show about Thomas Sowell?”

Craig lit up instantly.

“That's a million dollar idea!”

His excitement was as inspiring as it was infectious. I then relayed the idea to libertarian writer and podcaster Tom Woods, an avid theatre-goer who'd been a champion of me and my story. He was as electrified as Craig:

“You have to do this!”

My goal was a small crowdfunding campaign to obtain some living expenses for a few months as I wrote a draft of the play. Tom generously agreed to feature me on his podcast and inform his network of the idea. He even bought the sowellplay.com domain name.

“I did this for a friend who wanted to write a book, and we raised like $40,000,” he said. “Now, I can't guarantee that you'll get that much money, but we'll see.”

Tom furnished some copy. I revised it and made it mine. I shot and edited a short, funny video. And then I got cold feet. But Tom urged me onward.

Eventually, thanks to shares from massive influencers—including Scott Adams, Melissa Chen, and Konstantin Kisin, among others—as well as other generous benefactors, nearly 1,000 people backed the campaign to the tune of over $140,000—more than 14 times the original ask. By any measure that's a successful campaign.

But I was still afraid: I vowed to have a draft done in 6 months.

It's been a year.

Still no draft.

After the IndieGogo campaign closed, I spent 2024 pulling myself in many directions: remaining active on Twitter; trying to keep The Clifton Duncan Podcast going; trying to keep The State of the Arts alive; recording audiobooks and doing other side gigs; trying to research Dr. Sowell's prolific body of work; and on top of all that, trying to revive my acting career.

In trying to do everything, I achieved nothing.

In truth, losing the career I'd worked hard to build still haunted me. The insanity of the pandemic years—and what they revealed about humanity—were traumatizing. Worse, despite assurances from entertainment professionals that the waters were safe to swim in, I found barriers to re-entry into the business that weren't there before. It became clear that, despite the industry claiming to want to uplift black voices, mine was not welcome.

My drive died. I became deeply depressed. I numbed myself with marijuana and alcohol. The work stopped.

I had no clue what to do.

By Spring of 2025—a year after the launch of crowdfunding campaign—I began to find my way again.

Having been taken away from the Sowell project by prior commitments, I was finally free to focus on the play. I got a copy of Lajos Egri's classic The Art of Dramatic Writing, seeking to find a way to start. I'd already gotten great advice from a friend, a Tony Award-winning writer:

“Don't try to tell his whole life story. That's too much. Focus on one moment in his life and go from there.”

Having scoured Sowell's memoir A Personal Odyssey, his collection of private correspondences called A Man of Letters, and Jason Reilly's intellectual biography Maverick, I felt very strongly that the most sensible place to begin Sowell's story was not where some people expected—his humble beginnings in the North Carolina of the 1930s, or the streets of Harlem of the 1940s—but on an Ivy League campus in the 1960s.

The 1960s were as paradigm-changing for Dr. Sowell as they were for America. He left the decade radically changed from who he was when he entered it. First thinking he'd devote his life to teaching, he'd eventually become jaded by academia. Entering the decade an ardent Marxist, by its end he was converted. Hoping he'd found matrimonial bliss, by 1969 his first marriage was on the rocks and his son John wasn't talking—even at 4 years of age.

As all this was unfolding, America was in the throes of a racial revolution.

In April 1969 a group of armed black students seized Willard Straight Hall at Cornell University. Dr. Sowell happened to be an assistant professor there at the time.

His book Black Education: Myths and Tragedies (1974) includes details about the tensions that created (and facilitated) the volatile atmosphere on Cornell's campus: principled black faculty punished for political dissident; radical white faculty paving the road to hell with their good intentions; struggling black students anguished by failing in a racially charged environment; brilliant black students threatened for refusing to radicalize.

And Thomas Sowell—who was experiencing personal turmoil of his own—was in the middle of it all.

Drama is tension and conflict, and at Cornell in 1969 there was more than enough.

That is where this play must live.

CD

Sounds like a phenomenal starting point and place (Cornell, 1969)! Your friends advice is brilliant - regarding pick a dramatic moment - and start from there.

I'm developing a TV series drama about a man whose life is almost too accomplished to be true ( a freed ex-slave in the mid-late 1800s who became a real estate owner, gold mine operator, hotelier, helped free slaves on the Underground Railroad, wrote op-eds for abolitionist newspapers, helped get Abraham Lincoln elected, etc) In reading his biography and watching a documentary - I was almost NUMB with figuring out where to start the pilot episode...

But I took a really small but powerful moment - a turning point - both for him personally - and the world at large in the macro background - and jumped in.

I'm not done, but I feel I'm on the right path re: when I decided to start his story.

I can't wait to see what you develop. For what it's worth - if you need someone to read a draft or two and give feedback - I'd be excited. I've had work produced in NYC theatre, I've written TV and Film professionally - and was a writing coach for six years - for very prominent NYC playwrites, as well as TV and Film writers of note.

God speed. Don't stop - it's a muscle to be worked regardless of if the Muse strikes you on any particular day...

So looking forward to your play. I’ve loved Thomas Sowell for years. I have faith you will do his life justice. Thank you!!!